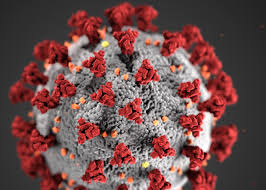

The COVID-19 virus intrusion is what Nicholas Taleb called a black swan event. Black swan events are a rare and unpredictable shock to a system with extensive consequences throughout the system. For example, the COVID-19 virus has already changed the way churches meet, the way food is secured, the way social interaction occurs, and has had a growing negative economic impact as businesses close and scale back their cost structures. Black swan events are defined by periods of high uncertainty and volatility.[1] It is the uncertainty of a black swan event that makes the recovery of “normal” a difficult target. This black swan event has imposed the social distancing strategy designed to limit the transfer of the COVID-19 virus from person to person. This has imposed a time of isolation for many people.

I have wondered about how to leverage the disruption and the isolation and what my horizon should be as a leader looking forward. Should I take a short view assuming the current disruptions are short term and the propensity toward stasis will nudge our experience back to a known sense of normal? Or do I take a long view and look at the current disruption and isolation as a push toward innovation? In my reflection, I was reminded of the work of Dr. Bobby Clinton, one of my mentors, on the way leaders develop. Specifically, how leaders mature. He identified several maturation processes one of which was isolation processing.

By maturation, Bobby meant the deep process that forces leaders to evaluate life and ministry for its deeper meaning. This evaluation reflects on what life is about and what ministry accomplishes. The purpose seems to be to shape one’s focus toward a whole lifetime of effect around what is ultimately important.[2]

Bobby recognized that isolation is the process by which a leader is set aside from normal activity so that the leader has an extended time in which to experience God in a new or deeper way. The isolation process in Bobby’s heuristic may be initiated voluntarily or involuntarily. Regardless of the way an isolation period is initiated the potential for experiencing a call to a deeper relationship and experience of God is possible. The lessons a person may experience in isolation times include dependence on God, learning about the supernatural, an urgency to accomplish their life purpose, deepening of one’s inner life, especially intercessory prayer, and lessons on spiritual authority.

The benefits of isolation are not automatic. They are dependent upon two variables, the amount of time spent in isolation and the response of the person in isolation.[3]

Among other things, this time of isolation exposes what Bolsinger describes as being imaginatively gridlocked in a pattern of trying harder at things that are not making an impact.[4] The challenge presented by the COVID-19 virus is an opportunity but to see the opportunity we must develop an adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity starts with the recognition that we don’t know and forces us to reevaluate what our core values are i.e., to strip away the traditions that have developed initially as support but now impediments to our mission or purpose. Are you willing to let go of “expertise” and learn as you go? Many of us conceptually recognize the need for adaptive capacity, now we are forced to step into it.

So, what is the time horizon you are using to evaluate the new normal? Is it just getting through the immediate crisis to go back to business as usual? Or, are you using the isolation to ask God to help you completely rethink how we do things, how to get at our real contribution of the truly important things? According to Bobby time and your response are the two variables that will determine whether you enter a new adaptive innovation or simply fall back into whatever normal was before the crisis.

[1] Source: https://thehill.com/opinion/finance/487579-coronavirus-and-price-discovery-during-black-swan-events. Accessed; 17 Mar 2020.

[2] J. Robert Clinton. Leadership Emergence Theory. Pasadena, CA: Barnabas Resources, 1989, 273.

[3] Clinton 273-386.

[4] Todd Bolsinger. Canoeing The Mountains: Christian leadership in uncharted territory. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015.