(An excerpt from the book, Change the Paradigm: How to lead like Jesus in Today’s World. Copyright 2015 by Raymond L. Wheeler. Used with Permission)

(An excerpt from the book, Change the Paradigm: How to lead like Jesus in Today’s World. Copyright 2015 by Raymond L. Wheeler. Used with Permission)

We sat around tables set up in a conference arrangement, and Professor Elizabeth Conde-Frazier sat just to my right. She paused long enough for me to rest from typing my notes. I realized after some moments that she was not going to restart her lecture immediately. I stretched my hands, repositioned them over the keyboard of my computer, and then glanced around the room. Every eye was aimed my direction. I turned to look at Dr. Conde-Frazier and caught a penetrating gaze. When our eyes met she inquired, “Why are you here?”

The question itself did not strike me as odd for two reasons. First, as a master teacher, she modeled a powerful and effective teaching style. She was a master at transitioning from content to dynamic reflection that refocused and honed our personal experience.

Second, as a middle-aged white guy in a culturally and gender diverse institution I often betrayed my own biases and upper middle class, suburban, and theologically conservative assumptions in my comments. This usually engendered a torrent of commentary from my academic peers on the evils of social privilege. A litany of historical references to abuse by those who held power and privilege often morphed into personal stories of marginalization or worse. I learned to listen to these stories as a process of education and reconciliation. I was, after all, a token representation of everything that social privilege represented in its best and its worst.

Power is not easy to possess when it is realized. The call to service Jesus gives makes power highly inconvenient. I would rather argue that it was not I who engaged in the kinds of social abuse described by my peers. However, as a leader I represent power and privilege—all leaders do. I did not grow up in poverty. I lived on the good side of town, and my parents remained married to one another throughout their lives. My upbringing was different from many of those in the classroom. I did not have to dodge gangs or violence each day growing up. I did not go hungry. I attended good schools and my parents could afford medical care. I was exposed to a great deal of cultural diversity as the son of a college professor. But the diversity I saw was sanitized—I saw it without its context. So, diversity was simply a curiosity—a distraction from the usual. I did not understand the experiences represented in the diversity I saw. Compared to so many others the word “privileged” does apply to me.

“I am not sure of the context of your question,” I responded.

“Why are you here,” she repeated with the same penetrating gaze. “Are you here to add to your social power and status through the acquisition of a doctorate or are you here to learn to serve?”

The question framed a tension that is common in a learning process and is common in engaging Christ. Is the acquisition or possession of social power de facto a contradiction of service? The inference beneath the frequently prickly comments of some of my academic peers in the program affirmed that many thought privilege and service were mutually exclusive. Many of them had suffered at the hand of social and ethnic prejudice. They arrived in this class by indefatigable persistence against all odds. Admittedly I did not understand the hurdles they had to cross to be there.

Clearly, a danger exists in the pursuit of power or added social currency. Blind pursuit of power leaves a wake of wrecked hopes and lives callously dismissed as mere collateral damage in the pursuit of ambition. But even if a person is not pursuing blind ambition the dilemma of injuring others while on the quest for justice does not go unnoticed by those hurt by the exercise of good intentions. A group of graduate students in Kenya helped me understand the damage of activism with good intentions. As we discussed ethics in leadership and the idea of reconciliation and justice, they pointed out that they did not object to justice. They objected to the way others defined justice for them. “We have a proverb here,” one of them stated. “When elephants make love, the grass gets crushed, and when elephants fight, the grass gets crushed.” From the perspective of the grass, the issue is not whether elephants fight or make love—the issue is that the elephants are unaware of the grass in the first place.

Leadership is complex. Effective leaders, those who know how to move people to work together toward specific objectives with passion and excellence, know that leadership requires more than style, skill, tools, experience, or power. Servant leadership works because of its underlying set of convictions about people, power, organizations, and success. For many it does not matter if the intentions of a leader are good or bad they still get crushed in the leader’s pursuit of success.

This reality is why defining servant leadership in the context of a leader’s life, work, organizational structure, spiritual development, and commitment to develop others is so important.

Don't be a zombie: why teams are a challenge

I hear it in almost every business I work with. I hear it in the classroom. It’s a collective groan and wave of murmuring when a team assignment is announced. It is that an implicit frustration that not everyone on the team will carry their own weight. It is the fear of team zombies.

I hear it in almost every business I work with. I hear it in the classroom. It’s a collective groan and wave of murmuring when a team assignment is announced. It is that an implicit frustration that not everyone on the team will carry their own weight. It is the fear of team zombies.

Various definitions of the word zombie adequately describe the kind of person everyone hopes will not appear on the team. Zombie: the body of a dead person given the semblance of life but mute and will-less, by a supernatural force, usually for some evil purpose. A person whose behavior or responses are wooden, listless, or seemingly rote: automaton.[1]

Team zombies show up to meetings and avoid talking and contributing. They fail to execute their assigned responsibilities, reduce trust, and seem to effectively suck the intelligence of the team deflating the team to levels of both incompetence and mediocrity. Team zombies are the paragon of Lencioni’s team dysfunctions.

What drives a zombie to act like a will less mute unwilling to take responsibility or fulfill assignments? In my work with teams, I have found four common contributors that turn normal people into zombies or as I like to call it, the forces of “zombification.”

Intimidation. The cause of “zombification” to correct is the result of someone being placed on a team with those who they feel are superior in skill, experience, and insight. It is the normal response of a novice. This occurs in healthy organizations in which a novice is routinely given an opportunity to work above their pay grade and experience level with a team of highly competent people in order to expose the novice to greater complexity in problem analysis and solution finding. I am encouraged when I see this kind of “zombification” occur because it is temporary and indicates that a person is in over their head and is learning to work with others who possess different and often greater experience and knowledge. It is also usually self-correcting because working around highly experienced and gifted individuals draws the best out of even the most awkward novice. If you work in this kind of environment take notes and appreciate the fact you are in an exceptional organization.

Fear of reprisal. Like intimidation, fear of reprisal is a “zombification” force that is rooted in the organizational culture. However, it is the diametric opposite of the kind of organizational culture that generates intimidation. Fear of reprisal results from having previously engaged critical thinking and innovation only to be shot down by others on the team or by the manager or owner because the idea challenged the status quo. Like intimidation this is frequently experienced in the novice who has joined an organization that acts far differently than they claimed. The novice has yet to discern what I call organizational double speak because they were blinded by the possibility of getting their first real paycheck so they didn’t pay attention to the clues they had all around them that the organization was a dysfunctional mess.

What are the clues of a dysfunctional organization? There are several to pay attention to: (1) use of passive verbs to define challenges e.g., sales are down. Sales or any other problem do not have a life of their own – the statement lacks causal information. (2) Hyper unanimity. People in great organizations share a similar vision but retain a unique personal perspective and even disagree at times. When I get around an organization that seems to have scripted answers to my questions rather than individual perspective I get suspicious. Typically there is a power broker behind the script that cracks the whip of fear. (3) Deflecting speech. When I ask questions that are deflected by the person in charge I also get suspicious. It usually indicates an organizational culture that lives in a manufactured reality – that reframe challenges so that a) no one is to blame or b) one singular cause is assigned to all failure.

Novices aren’t the only ones who experience dysfunctional organizational cultures. However, healthy novices get out. Unhealthy novices adapt and succumb to the practiced-identity-dissonance I describe below.

Conflict avoidance. This force of “zombification” is clearly inherent in dysfunctional organizations where conflict is viewed as detrimental to healthy interpersonal relationships. These kinds of organizations or departments exist as a co-dependent family system with defined roles and a key member who seems to dominate the emotional energies of the entire team. This person may not be the leader of the team but may hold the leader and the entire team captive to their emotional outbursts or threats. This is also a characteristic force of “zombification” in novice leaders or team members who have yet to understand that conflict is often the key to greater innovation and insight simply because in a healthy team conflict can represent the first step toward clarity and honesty in communication. Think about the old team life-cycle adage: form, storm, norm, and perform. Healthy conflict may be expressed in heightened emotions such as expressions of frustration or anger. Unhealthy conflict is expressed in belittling insults, and emotional shutdowns designed to dominate or suppress the opinions or participation of another.

Identity dissonance. Identity dissonance is a force of “zombification” characterized by a lack of clarity about who the person is in their strengths, behavioral patterns, or knowledge base. Identity dissonance is characteristic of a person who is unaware of the significant contribution they can make. Identity dissonance is expressed in two ways; practiced dissonance and unexplored dissonance.

Practiced dissonance occurs in those team members who exist in dysfunctional organizational cultures by keeping their head down and not making waves. These individuals do not have a clear grasp on their unique contribution, core skills, behavioral patterns, or unique gifts. They practice being zombies. They may complain about the repressive and toxic environment in which they work but they will never see the way their behavior passively condones the culture they say they hate. This kind of “zombification” is difficult to heal because it has become a protective excuse to avoid pain and a form of denial.

In contrast unexplored dissonance is a form of “zombification” that indicates a deep change is occurring in the person. It is, in the words of one of my mentors, a boundary time in development. This person faces uncertainty to the value of their contribution because they have engaged a position, or challenge, or period of development that calls for an expansion of their capacity. It is a temporary disorientation that ultimately finds resolution and with resolution a greater self-understanding, capacity to lead, and capability to contribute.

What is the conclusion then? I have said that internal (to the person) and external (corporate culture) forces exist that contribute to “zombification.” When analyzing your own hesitation to be a member of a team because the fear of “zombification” threatens to place inordinate responsibility and demands on your already precious time, I recommend a series of questions.

Is your hesitation rooted in the awareness that your organization is toxic? If so, why are you still there? Can you make a difference? (The answer to this depends on the power you have in the organization and the degree to which the organization is dysfunctional.) Who should you talk with to find a different organization to work for?

Is your hesitation rooted in the awareness that one of the forces of “zombification” have actually made their presence felt in your life and who can you talk to about it?

Is the “zombification” of one of your team members rooted in their being a novice? How can you mentor them to better performance?

Is your hesitation rooted in the fact you just don’t like being dependent on others to perform at your peak? Then check your arrogance. You have not succeeded alone up to this point. Is your avoidance of team participation actually a form of “zombification” in your own work behavior?

If you are stuck and you know you are a team zombie, find a coach or mentor and talk through how to become a contributor to the success of the team rather than a drain on the team’s performance. Work will be much more engaging and your interpersonal relationships much more fulfilling. Who wants to hang with zombies?

Finally, take responsibility to help the entire team raise their level of execution. If you refuse the force of “zombification” in your own life you can model for others how to do the same. But, don’t think you can model this from a posture of relational neutrality. You will have to talk about the subject and help others see how their behavior may, in fact, contribute to the very kind of work environment they hate. This doesn’t mean you must become a task master – it simply means you become a friend rather than a zombie.

[1] Source: http://www.dictionary.com/browse/zombie; Accessed 12 May 2017.

Take a deep breath, slow down – hiring doesn't need to be a pain

Hiring, none of my clients enjoy hiring. In fact, they strongly dislike the entire disruptive process of finding a new person. The process is fraught with risk, expense, and distraction (hidden costs). Hiring, however, is not like removing a band-aid, do not just rush through it thinking that reduces pain. Hurrying through the hiring process exponentially increases pain. Hiring is more like creating a fine wine. You need the right process, the right ingredients, and time to age. Which is to say, good hiring is as much about perspective as it is a good process.

Hiring, none of my clients enjoy hiring. In fact, they strongly dislike the entire disruptive process of finding a new person. The process is fraught with risk, expense, and distraction (hidden costs). Hiring, however, is not like removing a band-aid, do not just rush through it thinking that reduces pain. Hurrying through the hiring process exponentially increases pain. Hiring is more like creating a fine wine. You need the right process, the right ingredients, and time to age. Which is to say, good hiring is as much about perspective as it is a good process.

Here are some stats on hiring that SHRM recently published. örgen Sundberg, CEO of Link Humans, estimates that bad hires cost as much as $240,000. Several variables that go into calculating the cost to replace a bad hire in our experience. These include:

- Recruitment advertising fees

- Recruitment follow-up and review

- Staff time for interviews

- Relocation costs

- Training costs

- Reduced team performance

- Disruption across related projects

- Lost opportunity

- Assessment costs

- Placement services

- Litigation fees

A 2015 talent acquisition study from Brandon Hall Group and Mill Valley, Calif.-based Glassdoor concluded that the lack of a standardized interview process makes a company five times more likely to make a mistake in hiring compared to those companies with a standard process. Look at your process. Do you have one? What makes it work or why has it failed? What needs to change?

Ten percent of the respondents to one survey noted that new hires did not work out because they did not fit the culture of the organization. Oddly, determining cultural fit is typically one of the last steps many companies take in hiring. Since skills are easily assessed through any variety of validated skill assessment tools, it makes sense to spend more time on cultural fit. In my work with clients, appropriate skills sets are determined through communication skill, behavioral interviews, and skill testing. Communication skills are used as a preliminary test of employee capability. We provide instructions on how to follow-up by requesting response in writing. If a potential employee cannot put together professional email response they are dropped. A quick phone interview determines whether they have the presence that is needed.

Part of cultural fit is understanding the work behavior and stress behavior of the potential employee. I use the Birkman Method Signature report to look for who may make the best team fit. The Signature report from Birkman isn’t a cure-all, but it will accelerate how long it takes to understand how the potential hire will approach their work and your existing team.

Brandon Hall Group research reports that strong onboarding processes improve new-hire retention by 82 percent and productivity by over 70 percent. In contrast, companies with weak onboarding programs are more likely to lose new hires in the first year! One researcher suggested that the onboarding process should be a year-long mentoring process that routinely checks in on new hire adjustment and development.

Hiring is inconvenient, bad hiring is extremely inconvenient. Review your hiring process. The best time to make improvements in the way you hire new people is before you need to engage the process. Don’t wait until you are under the gun to find someone and whatever you do – don’t just look for a stop-gap. You will loathe the day you hurried through the process of hiring. On the other hand, if your organization is growing, hiring is a consistent need. In addition to the good process, a good mental shift is also helpful. Don’t look at hiring as a pain, look at it as part of your work to meet your customer needs with excellence.

If you are the owner or the hiring manager of your company build the kind of networks that allow you to be exposed to the best employees. Recruit even when you don’t have a position open at this very minute. Why wait? Think about what your organization needs next year and the year after, not just what is needed today. Remember that open positions actually offer an opportunity to rethink how work gets done. Look at your existing team first. Who is moving up? Who else needs to move out? If you have to do the work of hiring then look at your entire team and ensure that you have the best team for where your organization is going. Don’t fear change – embrace it.

I am always happy to sit down with you and talk through how your company finds and places new people. Give me a call.

Avoid the weariness trap

The single greatest challenge I see in the leaders I have known is the challenge of weariness that isolates them from their team. Leaders who are weary become inconsistent in the enforcement of policy and disengaged emotionally from their team.

I am often asked to help organizations develop new systems or to engage in remedial coaching for a poor performing employee. I have learned in these engagements to insert a condition. If I don’t work with the CEO or owner as well as the challenge employee or group I don’t take the engagement. Why? Because poor performance is rarely a single issue event.

The place leaders wear down the most is the place they can least afford i.e., staying engaged and staying consistent.

Like it or not employees or staff take their queue from the posture of the manager or executive to whom they report. It doesn’t take long for inconsistency on the part of the manager or executive to cascade through the system of their direct reports as lethargy, poor follow through, or even deliberate sabotage of the company’s objectives. It is fairly easy to empower a group or individual to engage their work when two things occur.

First, support the work of others with consistent application of existing policy whether it is informal (implicit as in past behavior) or formal (explicit as in an employee handbook and job descriptions). Set clear expectations and provide a consistent environment and people will generally exceed expectations. I watched an entire sales team languish in one company when one of the members of the team (the poorest performing member) was retained in a downsize over a long-term employee who was a better producer. Why? Because the employee was friends with the owner – they were a “project” of the owner. As a result, the entire team saw that reward for their effort was not a matter of their own work or mastery of their tasks but the result of the degree to which they curried the favor of the owner. There is no wonder then that better producers resented this setup and became unresponsive to doing any work outside of meeting the minimum number of tasks.

Second, recognize the negative impact of poor systems. Poor systems are not unusual in privately held companies where the owner still struggles with the concept of corporate sovereignty i.e., a system of control and policy that describes what can and cannot be done so that the organization becomes the sovereign rather than the owner. In many privately held companies, the owner is the first to violate the rules of operation that he demanded others live by. This situation is compounded by the fact owners often refuse to design a system so that control of the company can transition from his or her own activity to a clear operating process and people committed to executing on that process. Designing such a system takes work – it is the work of decentralizing power not just delegating tasks. That is what makes it risky and why it doesn’t happen on a whim. One mentor of mine was fond of pointing out that the first job of any leader was to develop other leaders. Owners who have this mentality focus their efforts on building a great company around a great system of policies and controls that allowed employees to fully engage their work. These owners develop others to step up to responsibility and commitment. On the other hand, if hard conversations are ignored or avoided leaders won’t be developed. A great company expects policies to be enforced. When a leader demonstrates that they can be intimidated or that they won’t consistently enforce policy then performance runs amok.

Both of these problems i.e., inconsistency and poor systems, contribute to leadership weariness.

First, leaders try to do the work of their entire team – their scope is too far reaching usually out of mistrust of others. This is a sure sign that the systems and controls that are needed to create a great company are missing. Instead of disciplined execution, these leaders run from fire to fire. People never know where this leader will land and resent the intrusion when they do because they are a flurry of activity and anxiety that contributes very little to the completion of the task. How many hats do you wear in your business or organization? Why? If your answer is that others just don’t have the commitment or the skill it is time to reassess your assumptions about your organizational structure and your hiring practice. Up the game or the game will eat you. Create systems and processes that ensure the right controls and the right permissions so that others can excel along with you.

Second, leaders often don’t know how to rest. They violate their own physical and mental energy by overexerting themselves for fear that others won’t perform. The fear part of this equation is answered in designing clear processes and accountability. The exhaustion part of this equation comes from a lack of time away. This kind of leader hovers over the time clock, stays late, arrives early and present him or herself as the paragon of productivity. In fact, they often duplicate their efforts, give contradictory commands, and overturn other people’s work then hasten to get them to do it again without significant changes. Day’s off and vacations are not optional. A tired leader often thinks he or she is demonstrating deep commitment – however, their short fuse, inability to critically assess problems and emotional detachment undermine the commitment of those working for them.

If things are broken reassess your systems and the degree to which you are developing leaders.

If you are weary, get away before you destroy your own success by harboring resentment toward those you blame for your weariness (usually the people closest to you who have no idea of what you are feeling – they just sense your displeasure).

Avoid the weariness trap

The single greatest challenge I see in the leaders I have known is the challenge of weariness that isolates them from their team. Leaders who are weary become inconsistent in the enforcement of policy and disengaged emotionally from their team.

The single greatest challenge I see in the leaders I have known is the challenge of weariness that isolates them from their team. Leaders who are weary become inconsistent in the enforcement of policy and disengaged emotionally from their team.The place leaders wear down the most is the place they can least afford i.e., staying engaged and staying consistent.

Like it or not employees or staff take their queue from the posture of the manager or executive to whom they report. It doesn’t take long for inconsistency on the part of the manager or executive to cascade through the system of their direct reports as lethargy, poor follow through, or even deliberate sabotage of the company’s objectives. It is fairly easy to empower a group or individual to engage their work when two things occur.

Both of these problems i.e., inconsistency and poor systems, contribute to leadership weariness.

First, leaders try to do the work of their entire team – their scope is too far reaching usually out of mistrust of others. This is a sure sign that the systems and controls that are needed to create a great company are missing. Instead of disciplined execution, these leaders run from fire to fire. People never know where this leader will land and resent the intrusion when they do because they are a flurry of activity and anxiety that contributes very little to the completion of the task. How many hats do you wear in your business or organization? Why? If your answer is that others just don’t have the commitment or the skill it is time to reassess your assumptions about your organizational structure and your hiring practice. Up the game or the game will eat you. Create systems and processes that ensure the right controls and the right permissions so that others can excel along with you.

Second, leaders often don’t know how to rest. They violate their own physical and mental energy by overexerting themselves for fear that others won’t perform. The fear part of this equation is answered in designing clear processes and accountability. The exhaustion part of this equation comes from a lack of time away. This kind of leader hovers over the time clock, stays late, arrives early and present him or herself as the paragon of productivity. In fact, they often duplicate their efforts, give contradictory commands, and overturn other people’s work then hasten to get them to do it again without significant changes. Day’s off and vacations are not optional. A tired leader often thinks he or she is demonstrating deep commitment – however, their short fuse, inability to critically assess problems and emotional detachment undermine the commitment of those working for them.

If things are broken reassess your systems and the degree to which you are developing leaders.

If you are weary, get away before you destroy your own success by harboring resentment toward those you blame for your weariness (usually the people closest to you who have no idea of what you are feeling – they just sense your displeasure).

How do you Stay Engaged as a Leader?

I have spent the year digging into the life of the biblical character David. I was drawn to David because much can be learned about how to survive the pressures of leadership when there is a way to get inside the head of a successful leader. That David was successful is apparent, he unified a loose confederation of tribes into a central government; he established the infrastructure needed to sustain a nation including the enormous task of shifting the “corporate culture” of the nation from one of tribal self-service and intrigue to one that engaged a sense of unified purpose and support. He survived several attempts to topple his reign and he engendered the kind of loyalty in others that gave them permission to speak the truth and express a willingness to put their lives on the line for him. Success alone isn’t that impressive, a lot of jerks are successful. What makes David’s success so amazing is that he consistently came back to the kind of character and ethical decision-making process that raised the character of the nation. He openly admitted his faults and openly changed for the better.

It is possible to get inside David’s head because he wrote a lot. David put his emotions, insights, fears, questions, distress, gratitude, and celebration. This is remarkable for two reasons. First, in my observation leaders who fail to express the full range of emotion ultimately derail into only anger and resentment. These leaders cannot see the impact of their behavior and emotion on others. They become toxic and abusive. Second, the leaders who exhibit emotional awareness and remain emotionally engaged are leaders who can then express a range of emotions appropriate to what they experience.

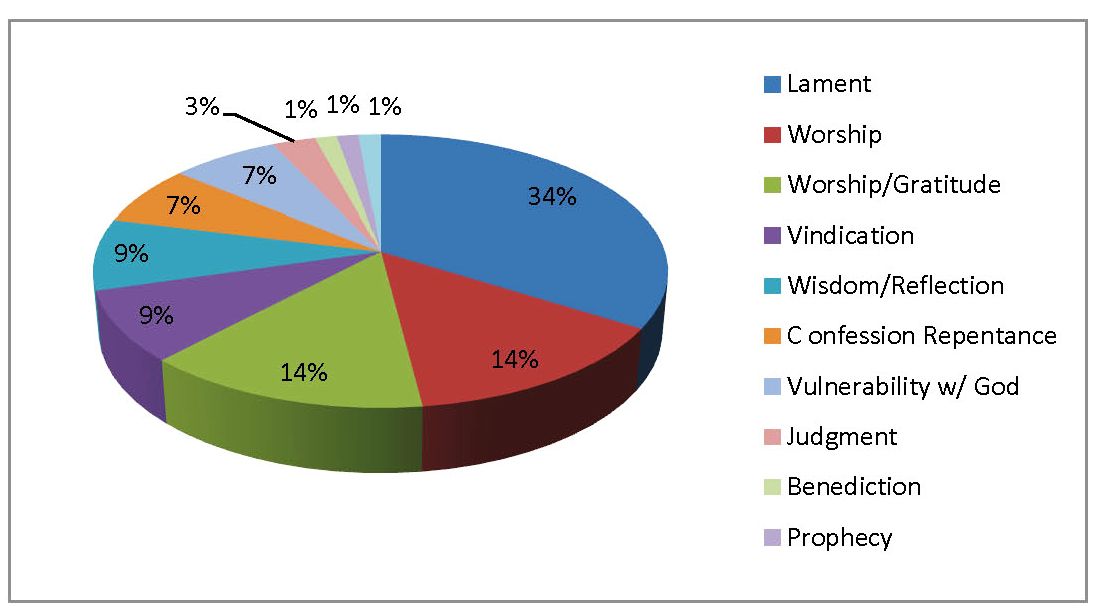

David wrote 71 Psalms that I analyzed for their major themes. The distribution of these major themes across the Psalms of David is illustrated in the chart below and defined in Table 1.

Chart 1: Themes in the Psalms of David

Three things jump out at me when I review the chart. First, notice the preponderance of lament in David’s writing. Over one-third of David’s Psalms were laments in the face of disaster, disappointment, danger, and loss. I like this because those who study leadership seem to rarely write about how leaders face disappointment, betrayal, loss, danger, and disaster. All of these experiences are part of leading which is why many sane people avoid jumping into a leadership role. David faced these things with an emotionally healthy expression of anger, grief, and howling. It’s a good lesson for leaders when they face the turbulence of leadership – get alone and have a good howl.

Second, David lived with a profound sense of purpose. It is meaningful because leaders who produce lasting results possess a transcendent awareness of purpose. They inspire others with it. It drives them to continue when every other aspect of their being may just want to throw in the towel. David worshiped and he worshiped with a sense of gratitude. He lived the practical, dirty, gutsy reality of leadership with a perspective that included a sense of the transcendent. This impacted his decision-making, his respect for the experience of others, and his decisiveness and compassion. Leaders devoid of purpose, leaders who have no real sense of the transcendent can fall prey to data pedantic that dehumanizes work and aims at efficiency in profit unaware of the stultifying impact on those who make profit happen.

Table 1: Definition of Terms

Theme

Description

Lament

Expressions of distress, grief, sorrow

Worship

Expressions of devotion, adoration, praise, and love for God.

Worship/Gratitude

Expressions of adoration, appreciation, and thankfulness.

Vindication

Desire for God’s help to clear from accusation, imputation, or suspicion.

Wisdom/Reflection

Expressions of what has been learned through experience.

Confession Repentance

Acknowledgement of a lapse in moral judgment and deficiency in behavior.

Vulnerability w/ God

Deliberate exposure of intent, dependency, and susceptibility.

Judgment

Request for God’s direct exercise of justice and punishment of evil.

Benediction

Innovcation of divine help, blessing, and guidance.

Prophecy

Insight to the future promise and action of God’s working.

Reflection on Mortality

Thought on the meaning of life in light of its ephemeral nature.

Third, the frequency with which David reflected on his experience and drew new insights into the present as he prepared for the future is impressive. The wisdom Psalms of David point to an element of healthy leadership i.e., healthy leaders learn from their experience and learning is defined by a change in behavior. I am surprised at the number of leaders who relive the same experience over and over from one company to the next, from one year to the next without every asking what has happened and why it continues. Some leaders operate like a tether ball running faster and faster with less and less a scope of influence until at last they hit the wall only to recoil and start all over again.

Thanksgiving is a good time to do some reflection as a leader. How emotionally healthy are you? Do you have an appropriate outlet for your emotions? Are you aware of your emotional health or distress? Learn from David and be a leader whose emotional awareness gets leveraged into new insights and deeper connections with your partners, employees, and clients.

How do you Stay Engaged as a Leader?

I have spent the year digging into the life of the biblical character David. I was drawn to David because much can be learned about how to survive the pressures of leadership when there is a way to get inside the head of a successful leader. That David was successful is apparent, he unified a loose confederation of tribes into a central government; he established the infrastructure needed to sustain a nation including the enormous task of shifting the “corporate culture” of the nation from one of tribal self-service and intrigue to one that engaged a sense of unified purpose and support. He survived several attempts to topple his reign and he engendered the kind of loyalty in others that gave them permission to speak the truth and express a willingness to put their lives on the line for him. Success alone isn’t that impressive, a lot of jerks are successful. What makes David’s success so amazing is that he consistently came back to the kind of character and ethical decision-making process that raised the character of the nation. He openly admitted his faults and openly changed for the better.

I have spent the year digging into the life of the biblical character David. I was drawn to David because much can be learned about how to survive the pressures of leadership when there is a way to get inside the head of a successful leader. That David was successful is apparent, he unified a loose confederation of tribes into a central government; he established the infrastructure needed to sustain a nation including the enormous task of shifting the “corporate culture” of the nation from one of tribal self-service and intrigue to one that engaged a sense of unified purpose and support. He survived several attempts to topple his reign and he engendered the kind of loyalty in others that gave them permission to speak the truth and express a willingness to put their lives on the line for him. Success alone isn’t that impressive, a lot of jerks are successful. What makes David’s success so amazing is that he consistently came back to the kind of character and ethical decision-making process that raised the character of the nation. He openly admitted his faults and openly changed for the better.

It is possible to get inside David’s head because he wrote a lot. David put his emotions, insights, fears, questions, distress, gratitude, and celebration. This is remarkable for two reasons. First, in my observation leaders who fail to express the full range of emotion ultimately derail into only anger and resentment. These leaders cannot see the impact of their behavior and emotion on others. They become toxic and abusive. Second, the leaders who exhibit emotional awareness and remain emotionally engaged are leaders who can then express a range of emotions appropriate to what they experience.

David wrote 71 Psalms that I analyzed for their major themes. The distribution of these major themes across the Psalms of David is illustrated in the chart below and defined in Table 1.

Chart 1: Themes in the Psalms of David

Three things jump out at me when I review the chart. First, notice the preponderance of lament in David’s writing. Over one-third of David’s Psalms were laments in the face of disaster, disappointment, danger, and loss. I like this because those who study leadership seem to rarely write about how leaders face disappointment, betrayal, loss, danger, and disaster. All of these experiences are part of leading which is why many sane people avoid jumping into a leadership role. David faced these things with an emotionally healthy expression of anger, grief, and howling. It’s a good lesson for leaders when they face the turbulence of leadership – get alone and have a good howl.

Second, David lived with a profound sense of purpose. It is meaningful because leaders who produce lasting results possess a transcendent awareness of purpose. They inspire others with it. It drives them to continue when every other aspect of their being may just want to throw in the towel. David worshiped and he worshiped with a sense of gratitude. He lived the practical, dirty, gutsy reality of leadership with a perspective that included a sense of the transcendent. This impacted his decision-making, his respect for the experience of others, and his decisiveness and compassion. Leaders devoid of purpose, leaders who have no real sense of the transcendent can fall prey to data pedantic that dehumanizes work and aims at efficiency in profit unaware of the stultifying impact on those who make profit happen.

Table 1: Definition of Terms

| Theme | Description |

| Lament | Expressions of distress, grief, sorrow |

| Worship | Expressions of devotion, adoration, praise, and love for God. |

| Worship/Gratitude | Expressions of adoration, appreciation, and thankfulness. |

| Vindication | Desire for God’s help to clear from accusation, imputation, or suspicion. |

| Wisdom/Reflection | Expressions of what has been learned through experience. |

| Confession Repentance | Acknowledgement of a lapse in moral judgment and deficiency in behavior. |

| Vulnerability w/ God | Deliberate exposure of intent, dependency, and susceptibility. |

| Judgment | Request for God’s direct exercise of justice and punishment of evil. |

| Benediction | Innovcation of divine help, blessing, and guidance. |

| Prophecy | Insight to the future promise and action of God’s working. |

| Reflection on Mortality | Thought on the meaning of life in light of its ephemeral nature. |

Third, the frequency with which David reflected on his experience and drew new insights into the present as he prepared for the future is impressive. The wisdom Psalms of David point to an element of healthy leadership i.e., healthy leaders learn from their experience and learning is defined by a change in behavior. I am surprised at the number of leaders who relive the same experience over and over from one company to the next, from one year to the next without every asking what has happened and why it continues. Some leaders operate like a tether ball running faster and faster with less and less a scope of influence until at last they hit the wall only to recoil and start all over again.

Thanksgiving is a good time to do some reflection as a leader. How emotionally healthy are you? Do you have an appropriate outlet for your emotions? Are you aware of your emotional health or distress? Learn from David and be a leader whose emotional awareness gets leveraged into new insights and deeper connections with your partners, employees, and clients.

What script are you reading from?

“What did he say?” Bill (not his real name) was eager to find out what his partner had talked to me about. Bill and Abe (not his real name) were in the middle of a fight that threatened the productivity of their employees and gave the whole company and uncomfortable edge – even their customers had picked up on the tension.

“What did he say?” Bill (not his real name) was eager to find out what his partner had talked to me about. Bill and Abe (not his real name) were in the middle of a fight that threatened the productivity of their employees and gave the whole company and uncomfortable edge – even their customers had picked up on the tension.Three questions successful people routinely ask themselves

I had the pleasure of addressing the incoming class at Bethesda University in Anaheim, California this morning. They are a wonderfully diverse student body, many of whom are the first generation to enter college. In my time teaching there I was privileged to hear the stories of change, courage, and the desire to give back to their communities. In thinking about what would both inspire and challenge them this morning I thought of three blunt and transformative encounters Jesus had with his disciples.

I had the pleasure of addressing the incoming class at Bethesda University in Anaheim, California this morning. They are a wonderfully diverse student body, many of whom are the first generation to enter college. In my time teaching there I was privileged to hear the stories of change, courage, and the desire to give back to their communities. In thinking about what would both inspire and challenge them this morning I thought of three blunt and transformative encounters Jesus had with his disciples.

The narratives of these encounters are stacked up together in Luke 9:46-55. In the first (v 46-48) Jesus addresses the idea of greatness. In the second (v 49-50) Jesus addresses the idea of synergy with others. In the third (v 51-56) Jesus addresses the subject of anger in the face of rejection. These three encounters frame the questions I find successful people ask themselves to remain focused on the important rather than the urgent. This kind of focus helps them see opportunity others simply walk past. And, it is this ability to see that seems to drop new opportunity at their doors step regularly. So, let’s look at the questions and how they work to generate focus and new ways of seeing.

What is your ambition?

The disciples clearly had ambition (a drive toward a new future and a trajectory away from a past). However, their ambition had gone down the road of power acquisition and prestige. Somewhere along the way, they began to run to the goal of dominance rather than destiny. This detour along the way doesn’t take a person toward their future – rather it reasserts the past as a diminishment to be avoided rather than a foundation on which to build a future. Those who are running from their past have not yet made peace with their past and end up running into an ever increasing intensity of shame and denial.

Jesus redirected the disciple’s debate by pointing to a child and asking them to receive or relate to the child. I think of my grandchildren who don’t care about the fact I have an earned doctorate, or that I own a successful company, or that I am recognized as an effect adjunct professor. All they know is that I engage them at their level with attentiveness, love, and a desire to see them succeed.

Jesus reduced the question about who is the greatest to a willingness to engage life like one engages a child. This generates a posture of learning v showmanship, curiosity v arrogance, and vulnerable v defensiveness. Refine your ambition – dream big AND do it as a learner, not an expert.

How do you see others?

Small minded people interpret knowledge as power and the means for exclusivity. Jesus redirected the disciples who shut down the effective efforts of some unnamed person flourishing in the works of God simply because that person wasn’t part of their “in-group.”

Jesus’ response had two parts. First, DON’T HINDER HIM. The success of others is not a threat – it is a point of potential synergy! If you view the success of others as a threat to your own power/prestige then you will never achieve the greatest part of your ambition. You won’t be a change agent you will be a toxic tyrant.

Second, Jesus’ lesson is powerful, listen to it. WHOEVER IS NOT AGAINST YOU IS FOR YOU! This is a significant shift in perspective and will keep you from being so afraid of loss that you fail to see friends. Highly successful people have large networks of highly successful friends. Why? They don’t view the success of others as a threat rather; they see the success of others as a potential point of synergy and momentum to their own ambition.

If you are proud about getting rid of others who threatened your own prominence, then competitors are about to eat your lunch. You got rid of the very people who would both accelerate and help sustain your own ambition.

What do you do with anger?

James and John were furious at the way the Samaritans refused to help them. They wanted revenge for the rejection and betrayal they felt. The reality is that in life rejection and betrayal happen. The question isn’t whether one has face rejection or betrayal it is whether they will engage in the ruinous circle of revenge or the virtuous circle of forgiveness. The cycle of anger and revenge is what destroys many communities and organizations and holds them in poverty and mediocrity.

You can choose to break the cycle of revenge and anger and be a healing force in your community or organization. If you want to transform your community or organization you won’t do it through anger and revenge – you will do it through forgiveness

Forgiveness is a process (or the result of a process) that involves a change in emotion and

attitude regarding an offender. Most scholars view this as an intentional and voluntary process, driven by a deliberate decision to forgive. Forgiveness possesses behavioral corollaries i.e., reductions in revenge and avoidance motivations and an increased ability to wish the offender well impact behavioral intention without obliging reconciliation. Forgiveness can be a one-sided process. Johnson defines forgiveness as “A willingness to abandon one’s right to resentment, negative judgment, and indifferent behavior toward one who unjustly injured us, while fostering the undeserved qualities of compassion, generosity, and even love toward him or her…” (Craig E. Johnson. Ethics in the Workplace: Tools and Tactics for Organizational Transformation, 2007, 116).

Conclusion

So, what are the three questions highly successful people often ask themselves?

- What is my ambition?

- How do I see others?

- What will I do with anger?

How do you answer these questions?

Refocus your energy!

One of the themes that emerging from my client conversations lately is the need to refocus. What do you do when you or your organization experiences gridlock and a lack of energy? Or when increased activities just don’t result in the desired ends? Being gridlocked shows up in three ways: (1) an unending treadmill of trying harder, (2) looking for answers rather than re-framing questions, and (3) either/and or thinking that creates false dichotomies.

One of the themes that emerging from my client conversations lately is the need to refocus. What do you do when you or your organization experiences gridlock and a lack of energy? Or when increased activities just don’t result in the desired ends? Being gridlocked shows up in three ways: (1) an unending treadmill of trying harder, (2) looking for answers rather than re-framing questions, and (3) either/and or thinking that creates false dichotomies.