I have had a growing discomfort with the label “evangelical” particularly in the current environment of its more nationalistic, right leaning, personality cult here in the United States that issues propositions that overtly contradict the message of Jesus Christ. I have struggled with how closely the current western evangelical world reflects the world of German Christianity pre-World War II as described by Bonhoeffer. Bonhoeffer, and others more recently, decried the church’s inability to adequately address the abuses and distortions of hyper-nationalism he labeled rooted in static thinking.

I have had a growing discomfort with the label “evangelical” particularly in the current environment of its more nationalistic, right leaning, personality cult here in the United States that issues propositions that overtly contradict the message of Jesus Christ. I have struggled with how closely the current western evangelical world reflects the world of German Christianity pre-World War II as described by Bonhoeffer. Bonhoeffer, and others more recently, decried the church’s inability to adequately address the abuses and distortions of hyper-nationalism he labeled rooted in static thinking.

“…static thinking is, theologically speaking, legalistic thinking….Where the worldly establishes itself as an autonomous sector, this denies the fact of the world’s being accepted in Christ, the grounding of the reality of the world in revelations reality, and there by the validity of the gospel for the whole world. The world is not perceived as reconciled by God in Christ but as a domain that is still completely subject to the demands of Christianity, or, in turn, as a sector that opposes its own law against the law of Christ. Where, on the other hand, what is Christian comes on the scene as an autonomous sector, the world is denied the community God has formed with it in Christ. A Christian law that condemns the law of the world is established here, and is led, unreconciled into battle against the world that God has reconciled to himself. As ever legalism flows into lawlessness, every nomism into antinomianism, every perfection into libertinism, So here as well. A world existing on its own, withdrawn from the law of Christ, falls prey to the severing of all bonds and to arbitrariness. A Christianity that withdraws from the world falls prey to unnaturalness, irrationality, triumphalism, and arbitrariness.”[1] (Emphasis mine.)

The so called culture wars engaged by evangelicalism has launched a battle against the world God has reconciled to God’s self with the result that evangelicals are often at a loss as to how to love their neighbor, demonstrate deliverance and healing, or walk with the wounded toward Christ because they are too busy decrying the world’s moral turpitude while ignoring their own moral impieties. There are times I have wanted to simply stop the evangelical merry go round and disembark to find a faith that exercises a practice of grace, intellectual reflection, repentance, and effective community engagement. I’m done with calls to support a particular political party or policy stands as authentication of my evangelical credentials, silence in the face of absurd parallelisms between our current president and biblical characters. I overtly reject the premise that recognizes the current president of the United States as the most Godly and biblical president I can expect to see in my life time.[2]

I ran across a book by Richard J. Mouw, former president of Fuller Theological Seminary (my alma mater) titled, Restless Faith: holding evangelical beliefs in a world of contested labels. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2019. Dr. Mouw asserts there are good reasons for keeping the label and not allowing rightist forces to co-opt it. My respect for Dr. Mouw’s scholarship and faith gave me pause to consider an alternative to leaving the evangelical fold and to work toward a revitalization of how we think. What follows is a summary of his main points.

Mouw grounds his definition of evangelical in David Bebbington’s four-part definition;

- we believe in the need for conversion – making a personal commitment to Christ as Savior and Lord;

- we hold to the Bible’s supreme authority – the sola scripture theme of the reformation;

- we emphasize a cross-centered theology – at the heart of the gospel is the atoning work of Jesus on the cross of Calvary;

- we insist on an active faith – not just Sunday worship, but daily discipleship

However, these four distinguishing marks need to be qualified. Mouw sees the need for a common theological label that differentiates the essential distinguishing marks from other branches of Christianity. Diagnosing the root of the challenge of how evangelicalism has been co-opted by right wing political agendas results in several hypotheses. Mouw quotes New York Times columnist Ross Douthat who sees the evangelical community is breaking apart in part because of a gap between evangelical intellectuals and the millions who worship in evangelical churches. Douthat writes,

“It could be that the views and attitudes on display in the recent support for rightist causes has really been there all along, without much of an interest in the kinds of intellectual-theological matters that have preoccupied the elites. If so, the elites will eventually go off on their own, leaving behind an evangelicalism that is ‘less intellectual, more partisan, more racially segregated’ – a movement that is in reality ‘not all that greatly changed’ from what it has actually been in the past.”[3]

Mouw doubts Douthat’s scenario. I don’t agree per se with Douthat’s characterization of thoughtful evangelicals as elites but I do agree that anti-intellectual and isolationist influences in evangelicalism have often diluted our effectiveness and placed us on the wrong side of social justice issues and in contradiction of missio Dei. The proponents of a cultural interpretation of evangelicalism (evidenced in the so-called culture wars) has made segments of the evangelical world more like syncretism than contextualism here in the west.

With an implied nod to the potential of syncretism, Mouw notes that none of us can claim to rightly have a Christian worldview. Rather he moves from a noun to a gerund i.e., the practice of Christian “worldviewing”. He commends the process of reflection as the Word illumines our way. In a proper sense evangelicalism has been in a slow process of deliberate and implied deconstruction of its assumptions about church life, community engagement, appropriate lifestyles etc., in response to the work of the Holy Spirit.

Mouw amplifies Bebbington’s concise definition through his own history of development as an evangelical. The main points that follow emerge from a combination of chapters which center around his major themes. Mouw’s insights provide a much clearer demarcation for defining evangelical over against either fundamentalism (which he doesn’t overtly define) and right leaning political persuasions.

- Evangelical means critically engaging faith. Raised in a fundamentalist setting that was heavy in anti-intellectualism, Mouw’s first engagement with exercising careful theological reflection was a book by Bernard Ram, A Christian View of Science and the Scripture the book spoke to his intellectual curiosity based on reason and faith. His exploration of Ram, Henry, and others in an emerging cadre of intellectuals of faith set the stage for his conclusion that he didn’t have to choose between intellect and faith. He engages a restless faith i.e., one that is willing to explore precritical ideas through the lens of a postcritical set of data and careful thinking.[4]

- Evangelical means believing the authority of the Scripture and doing the hermeneutical work needed to understand what it says. Mouw’s hermeneutics follows that proposed by Edward John Carnell (1959) and his presentation of the progressive revelation of the scriptures i.e., “…first the New Testament interprets the Old Testament; secondly, the Epistles interpret the gospels; thirdly, systematic passages interpret the incidental; fourthly, universal passages interpret the local; fifthly, didactic passages interpret the symbolic.” (32) A recent work by Volf and Croasmun add depth to what proper hermeneutical work is for me. They note that productive theological integration of various disciplines relies on a biblically rooted, patristically guided, ecclesially located, and publicly engaged theology, done in critical conversation with the sciences and the various disciplines of the humanities, at the center of which is the question of the flourishing life. In my observation many evangelicals do not know how to think theologically hence the move toward a fundamentalist populism that has conflated culture and the gospel.[5]

- Evangelical means possessing a historical grounding. “We evangelicals have inherited much from believers who ‘over time and across circumstances’ have been faithful to the gospel. When we fail to nurture those memories we can easily get caught up in ‘skimming over surfaces.’”(38) Mouw doesn’t recommend pure nostalgia, it is important to remember mistakes as well as successes – to be honest and transparent in our reflection of history so that the lessons we should carry forward are not lost in the tyranny of the urgent nor the tyranny of success and its pursuit. I add that it is helpful to read outside reflections on evangelical history as well. I found Frances Fitzgerald’s book, The Evangelicals: the struggle to shape America (2017) a helpful historical lens.

- Evangelicals are clear about sin in a way that avoids the trap of our self-actualization culture that sidesteps the work of the Holy Spirit on one hand and dwelling on guilty self-hood in a way that is inimical to spiritual flourishing on the other. How to engage this tension is a function of contextualization that takes seriously Hiebert’s concept of the excluded middle i.e., those issues about how we live out faith in the face of the systemic issues and challenges such as the sickness of a child, hunger, life threatening natural disasters etc. Hiebert’s concept makes room for the supernatural in facing these challenges and deals honestly with the limitations of the west’s scientific worldview in understanding the full scope of the good news of Jesus Christ.

- Evangelicals sing in worship and express reverence and mystery in lyrics and physical response such as the raising of hands. Communal worship is a hall mark of evangelicalism and serves as a collective theological memory in poetry and affirmation of faith. The hymnody (past and present) of evangelicalism is a significant part of theology as a mystery discerning exercise rather than a problem-solving exercise. (96) It is here that some of the messiness of theological reflection occurs. Evangelicals are not comfortable with messiness although an emerging cadre of theologians (men and women) are helping bridge the conversations we need to have on mystery. I have found it helpful to retain relationships with the liturgical traditions I grew up in who often have a much better handle on mystery.

- Evangelicals approach the communication of faith in a neighborly dialogue that reflects an outworking of Hiebert’s bounded and centered sets that simultaneously summons others to faith in Christ (belief as a boundary) while also observing the direction of their search (towards or away from Christ) regardless of their cultural and personal distance from Christ. This does not minimize careful accounts of doctrine but does so in a posture of empathetic learning. Hiebert’s conceptualization of centered and bounded sets was revolutionary for me. It gave me a way to reflect theologically on why I don’t approach the world with expectations that they behave like Christians before they meet Christ. I start with where they are and help and encourage their movement toward Christ and toward faith. The bounded set approach (read legalistic approach) that makes the world an enemy to be defeated only shows up the hypocrisy of withdrawal from the community around us. In every case I have see evangelicals withdraw from their community to avoid “sin” I have seen them ultimate end up in a concentrated expression of sins that nullify their calls for morality.

- Evangelicals expect “…regenerated hearts and minds to be clear about the truth. Confused theology – to say nothing of outright theological error – can cause serious damage in the life and mission of the church.” (116) Mouw finds challenges in both the Religious Right and conciliar ecumenism. There are issues that need fierce conversations (to borrow a phrase from Susan Scott) because they are core to the mission of God, in these evangelicals cannot be content to simply agree to disagree. But evangelicals cannot be content with division as usual, the priestly prayer of Jesus that we would be one summons us to find areas of common ground, to remnants engaged in relationships that require fierce conversations and to do so in the Character of Christ. “We need to be perplexed together. We need to rediscover the humility to be puzzled, the courage to engage the ambiguities and conundrums in our texts and look to each other to find the flashes and refractions of answers in places we least expect them.” (123)

- Evangelicals engage the public sphere as an active presence embodying biblical flourishing. The challenge in the rise of the religious right is that its engagement in social-political life is not particularly clear about what it means to be biblically faithful in its approach. Culture war mentality is a wrong-headed tactic. Much of evangelicalism has lost (or never had) Neo-Calvinist perspective of common grace i.e., that in the thoughts of pagan thinkers there is a strain of truth from God rooted in imago Dei. That the human mind though fallen is gifted by God and to refuse to accept truth produced by such minds is to dishonor the Spirit of God. (131) This recognizes that God never ceases God’s work among people – God’s Providence is active toward all people. In recognizing that the depravity of sin “…is total – it affects all aspects of our lives…is not the same as affirming absolute depravity – the teaching that every thought and deed of the sinful heart and mind is worthless in the sight of God.”[6] (142) In discussing the relationship of activism to government Mouw rejects the notion that all government authority is de facto faithful to its biblical mandate and ergo to be passively or actively supported. Evil, such as demonstrated by Hitler and the Nazis is to be rightly opposed. Mouw takes Paul’s words in Romans 13 as normative behavior for government, but where this norm fails resistance to evil is appropriate. In following Christ, we neither need to withdraw from or take over in exercising our influence.

- Evangelicals are committed to the importance of a personal (individual) faith in Jesus Christ. Though we recognize that individual salvation is not enough; the church must collectively address issues of injustice and public morality. Every person lives life coram deo e., before the face of God. This sobering reality of knowing and being known by God is not reducible to individualism but is a call to responsible community so that as God loves us, we love one another. It is also a call to confront evil expressed in “isms” which are already defeated in Christ e.g., racism, sexism, legalism etc.

Mouw takes up the work of wresting the name, “evangelical” away from those who have co-opted it in order to amplify the best theological heritage it represents. He is committed in the process to the reformed moto of ecclesia reformata semper reformanda. He does not propose a passive stasis or nostalgia, but active pursuit of God in fullness and truth.

I see the deconstruction about church life, community engagement, and appropriate lifestyles mentioned by Mouw as emanating from two forces. The first is a syncretism with the context of the United States. In this direction the evangelical assumptions about itself have become more and more comfortable with its equivalence to American exceptionalism and nationalism. The second is a deconstruction emanating from the work of the Holy Spirit challenging culture assumptions that draws the church into a clearer reflection of the ministry of Christ. The later is where I place the discussion of Mouw who himself reflects a maturing of perspective that results from his engagement with the word and the spirit of God.

I found a heuristic in Mouw’s book that gives me direction on how to retain a personal integrity in claiming to be evangelical and a basis on which to challenge the misuse of the word by those who co-opt “evangelical” for their political agenda. May God grant us the grace and love to be the church Jesus calls us to be in the world.

[1] Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. (2009) Ethics: Dietrich Bonhoeffer works volume 6. Clifford J. Green ed. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 60-61.

[2] Source: https://www.minnpost.com/eric-black-ink/2019/04/on-michele-bachmann-and-her-view-of-trumps-godliness/; Accessed 26 June 2019.

[3] Mouw 2019:10.

[4] Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. (2009) Ethics: Dietrich Bonhoeffer works volume 6. Clifford J. Green ed. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. Bonhoeffer again makes a important contribution. The opposite of a critically engaged faith is any one of the inadequate options identified by Bonhoeffer that oppose formation: Reason which cannot grasp the abyss of holiness or the abyss of evil; Fanaticism which assumes that the power of evil can be faced with purity of the will and principle; Conscience which attempts to fend off the power of superior predicaments only to be torn apart and settle for an assuaged versus good conscience to keep from despairing; Personal freedom that values necessary action over untarnished conscience, fruitful compromise over barren principle, or radicalism over barren wisdom of a middle way consent to bad to avoid the worse unable to recognize that the worse they seek to avoid may be the better one; Private virtuousness that does good according to abilities but necessarily renounces public life in the self-deception necessary to remain lean from the stain of responsible action in the world. “In all that they do, what they fail to do will not let them rest.” (80)

[5] Miroslav Wolf and Matthew Coasmun. (2019) For the Life of the World: theology that makes a difference. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 82.

[6] Miroslav Wolf and Matthew Croasmun. (2019) For the Life of the World: theology that makes a difference. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 69. “The image of the home of God as an abiding relation between God and the world fits well with two great images bookend the Bible. Both are images of the creations’ wholeness and flourishing. …the verdant garden (Gen. 2:4-3:22)…the thriving (and verdant) city (Rev. 21:1-22:7).” This integration and the point of human flourishing as a result of relationship with God is a theme amplified by Wolf and Croasmun that illustrates integration and common grace.

I have had a growing discomfort with the label “evangelical” particularly in the current environment of its more nationalistic, right leaning, personality cult here in the United States that issues propositions that overtly contradict the message of Jesus Christ. I have struggled with how closely the current western evangelical world reflects the world of German Christianity pre-World War II as described by Bonhoeffer. Bonhoeffer, and others more recently, decried the church’s inability to adequately address the abuses and distortions of hyper-nationalism he labeled rooted in static thinking.

I have had a growing discomfort with the label “evangelical” particularly in the current environment of its more nationalistic, right leaning, personality cult here in the United States that issues propositions that overtly contradict the message of Jesus Christ. I have struggled with how closely the current western evangelical world reflects the world of German Christianity pre-World War II as described by Bonhoeffer. Bonhoeffer, and others more recently, decried the church’s inability to adequately address the abuses and distortions of hyper-nationalism he labeled rooted in static thinking.

I sat with friends of mine, both of whom are highly capable leaders in an international non-profit organization. Over the course of our conversation, they described their weariness and exhaustion as it relates to the demands of their current assignment. I listened to their story and noted that they danced around the subject of their director. They were careful to express their respect for their director whom they described as a high-capacity leader. What intrigued me in the conversation was the mixed messages I heard. On the one hand, they expressed frustration with their director over his consistent micro-management and unfinished initiatives. Every couple of weeks seemed to render a new “strategic” initiative that demanded everyone’s attention. Each new initiative had little connection to the one before it and never took into account the expenditure of financial and human resources needed to accomplish it. I could not make out a grand plan or objective in any of the initiatives they described. On the other hand, they praised his high capacity for vision and initiative. They spoke in lofty terms about how he worked on a minimum of three devices at once and endured a grueling seven day a week schedule. They described him as warm and caring and committed. Then they described him as manipulative and domineering.

I sat with friends of mine, both of whom are highly capable leaders in an international non-profit organization. Over the course of our conversation, they described their weariness and exhaustion as it relates to the demands of their current assignment. I listened to their story and noted that they danced around the subject of their director. They were careful to express their respect for their director whom they described as a high-capacity leader. What intrigued me in the conversation was the mixed messages I heard. On the one hand, they expressed frustration with their director over his consistent micro-management and unfinished initiatives. Every couple of weeks seemed to render a new “strategic” initiative that demanded everyone’s attention. Each new initiative had little connection to the one before it and never took into account the expenditure of financial and human resources needed to accomplish it. I could not make out a grand plan or objective in any of the initiatives they described. On the other hand, they praised his high capacity for vision and initiative. They spoke in lofty terms about how he worked on a minimum of three devices at once and endured a grueling seven day a week schedule. They described him as warm and caring and committed. Then they described him as manipulative and domineering.

When thinking about leadership through a theological lens it helps to be aware of the impact of one’s worldview on the process. We don’t think in a vacuum but in the context of the values, allegiances, and assumptions that make up the core of our worldview. So, approaching a theological reflection on what constitutes leadership is a process that requires both self-awareness and humility.

When thinking about leadership through a theological lens it helps to be aware of the impact of one’s worldview on the process. We don’t think in a vacuum but in the context of the values, allegiances, and assumptions that make up the core of our worldview. So, approaching a theological reflection on what constitutes leadership is a process that requires both self-awareness and humility. It isn’t uncommon today to find remnants of the mindset of the industrial revolution in how the church thinks about structure. The mechanistic assumptions so predominate in business and non-commercial structures throughout the 20th century often seeped their way into church governance here in the west in the adoption of a corporate organizational authentication for tax purposes. The emergence of the church growth movement contributed to this same mechanistic set of assumptions in that it often uncritically adopted effectiveness driven assumptions that placed relationships in a subordinate position to growth and self-preservation in the church. This propensity to mechanize organizational structures to gain efficiency and effectiveness fall short in that they stumble over the reality that people are involved. One business writer commented that a well-known shoe company’s heavy investment in TQM was undone by one guy in the order fulfillment department who purposely stuffed two right foot shoes or two left foot shoes in a single box. When asked why he was doing this he responded that his manager had treated him poorly and his actions were revenge because his manager’s bonus depended on consistently accurate order fulfillment.

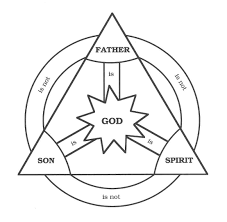

It isn’t uncommon today to find remnants of the mindset of the industrial revolution in how the church thinks about structure. The mechanistic assumptions so predominate in business and non-commercial structures throughout the 20th century often seeped their way into church governance here in the west in the adoption of a corporate organizational authentication for tax purposes. The emergence of the church growth movement contributed to this same mechanistic set of assumptions in that it often uncritically adopted effectiveness driven assumptions that placed relationships in a subordinate position to growth and self-preservation in the church. This propensity to mechanize organizational structures to gain efficiency and effectiveness fall short in that they stumble over the reality that people are involved. One business writer commented that a well-known shoe company’s heavy investment in TQM was undone by one guy in the order fulfillment department who purposely stuffed two right foot shoes or two left foot shoes in a single box. When asked why he was doing this he responded that his manager had treated him poorly and his actions were revenge because his manager’s bonus depended on consistently accurate order fulfillment. Theological propositions and discussion are often seem detached from the work-a-day world in the way we think. That doesn’t mean however that theological thinking is irrelevant to our day to day existence. Consider the doctrine of the Trinity. Work that reflects the nature and agenda of God, is shaped by the wholeness, uniqueness, oneness, and clarity of God’s triune nature. God’s triune nature, evident from the opening pages of the scripture, serves as a tutorial for one’s personal identity and expectations for how ministry should work and the collective identity of the local expression of the church.

Theological propositions and discussion are often seem detached from the work-a-day world in the way we think. That doesn’t mean however that theological thinking is irrelevant to our day to day existence. Consider the doctrine of the Trinity. Work that reflects the nature and agenda of God, is shaped by the wholeness, uniqueness, oneness, and clarity of God’s triune nature. God’s triune nature, evident from the opening pages of the scripture, serves as a tutorial for one’s personal identity and expectations for how ministry should work and the collective identity of the local expression of the church.