I was asked recently, “Do you think horrendously evil people could get into heaven? You know, people like murderers, rapists, child molesters, and war criminals.”

“I think it’s the wrong question,” I answered.

“Why?” She sat looking surprised and puzzled by my response. She has listed an undeniably repulsive list of criminal actions.

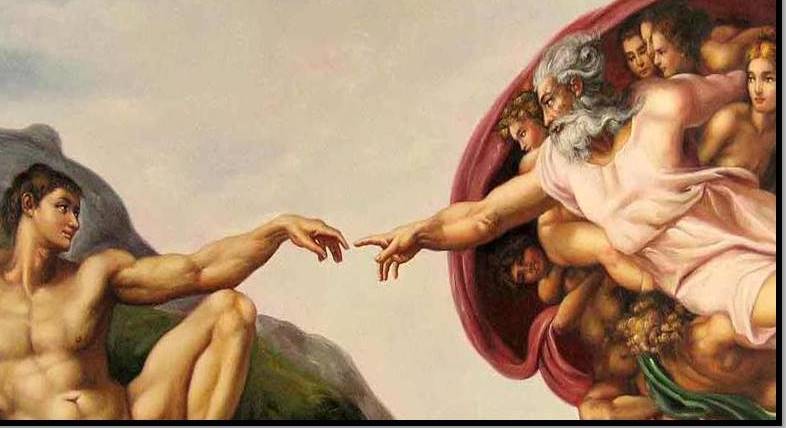

“It seems to me that the criteria Jesus talked about most, what he looked for most in the people who came to him, was transparency about their condition,” I said. “Look,” I continued, “Jesus said he didn’t come for the healthy; he came for the sick. The healthy don’t need (or don’t think they need) a physician.”

In my pastoral work, I have sat listening to stories of all kinds of deep, horrific behaviors, failed relationships, scarring from parental abuse, wounds from the physical abuse of a spouse, along with stories of addictions to drugs, sex, and adrenaline. It never ceased to be surprising that when I either just repeated what I had heard or extrapolated the source of pain from the poorly veiled descriptions of the congregant, their mouths would drop open, and they’d exclaim, “How do you know that?”

I learned to respond gently, “You just told me.”

In reading through the history of our founding as a nation, the political observations of the Machiavellians, the records of congressional debate, or the policy debates of political operatives, either contemporary or historical—as well as the personal correspondence of religious figures, I have come to see that humans have a grasp of the damage we inflict on one another. We are inadvertently transparent with people we feel safe around when we have consumed enough alcohol or when we believe we have a guarantee of privacy. It is unsurprising to find our behavior and words mirrored by those we consider unimportant or inattentive.

I have concluded that God will need to exert no more effort than repeating what we have said or rationalizing to exercise judgment against us. We find the idea of exposure and judgment appalling; whose standard can stand the test of objective judgment? It turns out that we routinely condemn ourselves by openly acknowledging that we know what we are doing is wrong, but because it works to our benefit, even if others are hurt, we do it anyway.

It turns out that humans are not that sophisticated or adept at hiding their errors. Well, at least until they are openly exposed to public scrutiny. Then, we become masters of gaslighting, red-herring arguments, and ad hominem justifications.

Families have secrets, nations have secrets, organizations have secrets, and businesses have secrets; what a silly game we play attempting to deny systemic bias, racism, economic inequity, social inequities, and legal manipulations at the root of our histories and our secrets.

Here is what makes the gospel of Jesus so revolutionary, unnerving, and revealing: Jesus asks us to admit what we attempt to conceal and, in that admission, to allow his love to begin a transformative work in us. Who gets in is simple, but it has little to do with creeds, formulas, or statements of belief. Will you open your secrets to the one who brings both exposure and healing through his resurrection from the dead? Will you exercise the humility needed to learn to walk through life with a different set of values, assumptions, and allegiances? You can’t pretend to be honest. You can pretend to be religious to everyone except those who know you best and have been impacted by your poor decisions.