When thinking about leadership through a theological lens it helps to be aware of the impact of one’s worldview on the process. We don’t think in a vacuum but in the context of the values, allegiances, and assumptions that make up the core of our worldview. So, approaching a theological reflection on what constitutes leadership is a process that requires both self-awareness and humility.

When thinking about leadership through a theological lens it helps to be aware of the impact of one’s worldview on the process. We don’t think in a vacuum but in the context of the values, allegiances, and assumptions that make up the core of our worldview. So, approaching a theological reflection on what constitutes leadership is a process that requires both self-awareness and humility.

A culture’s view of power distance, certainty/uncertainty, masculinity/femininity, time orientation, and individualism/collectivism represent the factors that make up cultural constructs of what constitutes leadership.[1] These cultural factors are implicit. A practical theology of leadership recognizes (1) the cultural differences that go into defining what appropriate leadership looks like and (2) the dissonance in perspective that is certain to follow the transformative work of the gospel. This transformative work in collaborating across worldviews works both ways necessitating the need for a strong self-awareness and willingness to learn about and from others prior to making generalizations about leadership effectiveness or ineffectiveness.

The New Testament often utilizes metaphors to lay a foundation for defining leadership. Peter, for example, writes, “I exhort the elders among you to tend the flock of God that is in your charge, exercising the oversight, not under compulsion but willingly, as God would have you do it – not for sordid gain but eagerly. Do not lord it over those in your charge, but be examples to the flock.” (1 Peter 5:1-3 NIV)

The use of the shepherd metaphor quickly identifies leadership as a servant role. Sure, a shepherd is in charge of sheep but her primary assignment is the care of sheep. Peter draws a picture that can challenge or affirm cultural factors that define leadership.

Some cultures maintain a strict hierarchical relationship or high power distance between follower and leader. Peter doesn’t argue the extent to which leaders and followers should relate in a peer or subordinate/superior relationship. He does insist that leaders not repress or deride their followers. I can walk onto a Korean campus and observe congregants bowing to their pastor. Is this appropriate from my cultural perspective? No, it’s surprising – even off-putting. However, in paying attention to the relationship I see the deep care and respect that is mutually given in this act. At issue isn’t the form but the transformation of values that inform the form.

Femininity/masculinity is also addressed. Who should lead? Can women lead men? The imagery of a shepherd is not restricted to male or female. Even in the Bible cultures varied in whether men or women cared for sheep. The point is that the imagery of Peter plays well to either male or female leadership roles and calls for the same approach to servant leadership in submission to God.

Good practical theology utilizes imagery as a starting point for insight amplified through cultural lenses that are both sufficient and incomplete. When cultures, even distinctly different cultures, approach the scripture with a heart to learning (the essence of discipleship), both can learn from the other and both will experience the affirmation and challenge of their cultural assumptions.

[1] Geert Hofstede. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 2001

How the nature of relationship intersects with the organizational structure found in the local church

It isn’t uncommon today to find remnants of the mindset of the industrial revolution in how the church thinks about structure. The mechanistic assumptions so predominate in business and non-commercial structures throughout the 20th century often seeped their way into church governance here in the west in the adoption of a corporate organizational authentication for tax purposes. The emergence of the church growth movement contributed to this same mechanistic set of assumptions in that it often uncritically adopted effectiveness driven assumptions that placed relationships in a subordinate position to growth and self-preservation in the church. This propensity to mechanize organizational structures to gain efficiency and effectiveness fall short in that they stumble over the reality that people are involved. One business writer commented that a well-known shoe company’s heavy investment in TQM was undone by one guy in the order fulfillment department who purposely stuffed two right foot shoes or two left foot shoes in a single box. When asked why he was doing this he responded that his manager had treated him poorly and his actions were revenge because his manager’s bonus depended on consistently accurate order fulfillment.

It isn’t uncommon today to find remnants of the mindset of the industrial revolution in how the church thinks about structure. The mechanistic assumptions so predominate in business and non-commercial structures throughout the 20th century often seeped their way into church governance here in the west in the adoption of a corporate organizational authentication for tax purposes. The emergence of the church growth movement contributed to this same mechanistic set of assumptions in that it often uncritically adopted effectiveness driven assumptions that placed relationships in a subordinate position to growth and self-preservation in the church. This propensity to mechanize organizational structures to gain efficiency and effectiveness fall short in that they stumble over the reality that people are involved. One business writer commented that a well-known shoe company’s heavy investment in TQM was undone by one guy in the order fulfillment department who purposely stuffed two right foot shoes or two left foot shoes in a single box. When asked why he was doing this he responded that his manager had treated him poorly and his actions were revenge because his manager’s bonus depended on consistently accurate order fulfillment.

Similarly, church leaders can tell their own stories about how one person’s or pastor’s vindictiveness held the entire organizational structure of a congregation hostage and leveraged a mechanistic structure to redefine reality or expectations of what the community of the church should be.

What makes the church so unique is that Jesus set the cornerstone of the church’s structure firmly in healthy relationships. Jesus said, “This is to my Father’s glory, that you bear much fruit, showing yourselves to be my disciples. As the Father has loved me, so have I loved you. Now remain in my love. If you keep my commands, you will remain in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commands and remain in his love.” (John 15:8-10)

Jesus outlines the task (remain in love) and the outcome (bear fruit) that make up the parameters of the church’s organization. Based on what Jesus modeled, love (or the organizational structure of the local congregation) is characterized by truth-telling, forgiveness, support, instruction, insight, inquiry, missional focus, and developmental bias. Love is not an afterthought or optional component to the relationships Jesus expected of the disciples as they continued his ministry. Love and its characteristics are the core feature that determines the legitimacy of the church.

Relationships are not an intersection in the organizational structure of the church they are the constituting frame that allows for the diversity of gifting, outcomes, and methods inherent in the works of God operating through the church. Relationships define the church’s purpose and its method. For example: does the organization accept responsibility i.e., bear fruit as outlined in Luke 4:18-19? Does the organization evaluate its context and behavior with truthfulness? Does the organization generate restored relationships, maturing behavior, continuous insight into what God is doing? If relationships serve only to intersect with a structure that is built on some other foundation (e.g., mechanistic) then relationship fails to be the nucleus and becomes a secondary add-on that is not elemental to effective and efficient operational systems. Organizational structures that push relationships to a secondary status inevitably become toxic and a contradiction to missio Dei.

So, how do you functionally define the structure of your congregation? Perhaps it’s time to sit with your leadership team and review what makes the structure of your congregation really tick.

How does the nature of God shape our work?

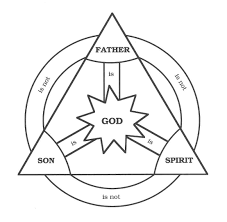

Theological propositions and discussion are often seem detached from the work-a-day world in the way we think. That doesn’t mean however that theological thinking is irrelevant to our day to day existence. Consider the doctrine of the Trinity. Work that reflects the nature and agenda of God, is shaped by the wholeness, uniqueness, oneness, and clarity of God’s triune nature. God’s triune nature, evident from the opening pages of the scripture, serves as a tutorial for one’s personal identity and expectations for how ministry should work and the collective identity of the local expression of the church.

Theological propositions and discussion are often seem detached from the work-a-day world in the way we think. That doesn’t mean however that theological thinking is irrelevant to our day to day existence. Consider the doctrine of the Trinity. Work that reflects the nature and agenda of God, is shaped by the wholeness, uniqueness, oneness, and clarity of God’s triune nature. God’s triune nature, evident from the opening pages of the scripture, serves as a tutorial for one’s personal identity and expectations for how ministry should work and the collective identity of the local expression of the church.

Personal identity is that foundation from which all of us serve. How we see ourselves, understand our own nature, and define our strengths is the essence of our definition of ministry. Our nature reflects the triune nature of God in that we exist as corporeal creatures that can reason and think about transcendence in purpose and meaning. Starting from the Trinitarian nature of God who exists without self-contradiction is a far better beginning for self-understanding than the dualism our culture inherited from the Greeks. The challenge of a dualistic approach is the denigration of rather than engagement of our corporeal existence. Evangelicals have wrestled long and hard about how to live in a body and maintain a sense of holiness and wholeness – but they wrestled with the idea of separateness or contradiction rather than integration. That God took the form of a human in Christ and lived in a way that flourished in a relationship with God and others models an integrated way of thinking about self. Being human, Jesus lived with all of the drives, hormones, distractions, temptations, and limitations of a corporeal existence. It remains then for us to accept that the body is not an albatross hanging around the neck of our spirituality but the foundation that gives us the capacity for relationship, interaction, and moral reasoning in the quest of meeting the needs of the body.

Expectations for how ministry should work are seen in Christ who modeled humanness filled with the Spirit of God. Foundationally ministry in Jesus’ model is responsive, “Very truly, I tell you, the Son can do nothing on his own, but only what he sees the Father doing; for whatever the Father does, the Son does likewise.” (John 5:19 NIV) We are not called upon to do God’s work solely with the strength, abilities, and drives of our corporeal existence. We are called upon to participate with God in the power of God’s being in a new relationship with the Holy Spirit. The agenda and the capability to impact humankind at its deepest and noblest level is God’s. Here ministry becomes an adventure of response to God the Holy Spirit that simultaneously confronts the powers that imprison the human condition to servitude and unleashes wholeness that washes over people physically, mentally, and spiritually. We are those who are truly alive. We are also truly present with God and with others. We see God’s works, we see others. The combination is transformative. The capability to engage this relationship is the gift of the Holy Spirit.

In the triune nature of God, we also have a model for how the collective identity of the local church can function in its variety of gifts, a variety of ways to serve, and a variety of operations. The fundamental declaration of the Trinity is, “Hear, O Israel! The Lord our God, the Lord is one!” (Deuteronomy 6:4 NASB) This unity that finds no room for competition, one-upmanship, or withdrawal is the eschatological summons of the local church to live out its fullness in the gifts inherent in its members. We are diverse in gifting, service, and effect but one body. Moving as one has the potential of impact on our world that a diffused or contending intramural existence can never have.

The Trinity shapes our sense of identity, our sense of capacity, and our sense of belonging and interdependence. To the extent, we engage the Triune nature of God in vulnerable repentance and obedience the church emerges as a holistic expression of God’s love and power. To the extent we ignore or diminish the triune nature of God we become irrelevant – just another player in the field of our pluralistic society that has just another truth claim without power.