We Saw it in the Arab Spring – How about a Corporate Spring?

You say you want a revolution

Well, you know

We all want to change the world[1]

The events of the Arab Spring affirm the observation that revolutions do not start at the top where the past and tradition is especially venerated – revolutions start at the bottom where the most diversity and possibility of broad-based adoption. But the Arab Spring could dwindle into narcissistic self-absorption like many of the “revolutionaries” of the 1970s in the United States who are now near retirement some of them wondering what happened to the idealism of their youth.

I was talking to a more experienced friend of mine about the challenges I faced in one organizational context in which I work. “You need,” he said after listening for while, “to read Gary Hamel’s book.”

He loaned Leading the Revolution and I have thought about a couple of the insights that live between the covers of this fascinating thesis.

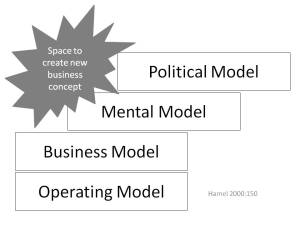

Hamel insists that in business (or any organization) the responsibility for innovation must be broadly distributed. I know from experience that the caveat is that those at the top typically derail attempts at broadly distributing responsibility for innovation as a means of protecting precedent (the prerogative of a few). In fact when operating models, business models, mental models and political models are in perfect alignment then the chance of innovation breaks down under the pressure to silence dissenters who threaten the status quo and the rewards inherent in being at the top.

Nurturing innovation requires that the organization’s mental model (deeply cherished beliefs) be challenged (pushed out of alignment with the business model) so that assumptions can be rethought. This however is not possible without first throwing the political model (distribution of power) out of alignment long enough to redistribute power so innovation can take hold. If power remains narrowly distributed at the top then the chance of successfully innovating from the bottom is next to impossible. This gives me pause to think about (1) how I have acted when I have been at the top and face dissenters who want to review how we do things and (2) how I manage the political power of organizations in which I do not exist at the top.

Figure 1: Creating Space for Business Concept Innovation[2]

So what is it that moves the mental and political models of an organization to make room for innovation as illustrated in Figure 1?

It takes two things to push mental and political models off-balance enough to introduce innovation according to Hamel: imagination and passion. The risk is the potential for political backlash (e.g., Bashar al-Hassad in Syria during the Syrian uprising of 2012). However, without becoming an imaginative and passionate activist unleashing innovation has little or no chance of occurring. Hamel makes an important point about becoming an activist in an organizational sense:

Activists are not anarchists. They are, the “loyal opposition.” Their goal is to create a movement within their company and a revolution outside in.[3]

In discussing activism in a purely organization sense, activists are committed to their company and to a cause that is at odds with pervading values or practices within the organization. Activists can behave responsibly and be a source of alternative ideas according to Hamel. Activists refuse to fit in on the one hand and live out street-smart pragmatism on the other hand. It is this second point – street smart pragmatism – that is often missing in inexperienced activists. They fail to see the potential backlash or pitfalls inherent in activism and so become the walking wounded who give up because they miscalculated the severity of the backlash.

So why care enough to engage in the behaviors of an activist? Hamel offers three compelling reasons:

- A person needs to live and work with purpose over and above their paycheck. Research demonstrates that those people who experience flow are also people who work out of a sense of purpose.[4]

- The organization is not “them” – it’s you. Whining about “them” is simply an excuse to justify inaction.

- You owe activism to your friends and colleagues – they deserve to make a very cool difference in the world.

Conclusion

Many of the leaders I work with both in the class room and in the board room can profit from this insight by Hamel. They don’t want to be an empty suit or disillusioned has-been. On the other hand some people simply don’t want to risk the potential backlash nor the work needed to engage in true innovation. How about you? Are you an imaginative and passionate contributor to purpose and meaning in work?

Here is another question, what if you are at the top? Are you ready to be an activist? What does it mean for those who follow you? What does street smart pragmatism look like for you around your board or other stake holders? Remember, your employees and colleagues deserve to make a very cool difference in the world.